Climate Migration: When the Planet Forces Us to Move

Climate change is no longer a distant threat—it’s a lived reality. Rising sea levels, extreme weather events, and prolonged droughts are increasingly forcing people to leave their homes in search of safety and stability. This global phenomenon, widely referred to as climate migration, is reshaping societies in ways we are only beginning to understand. Unlike traditional migration, which is often driven by economic opportunities or conflict, climate migration arises from environmental pressures that make it impossible—or too dangerous—for communities to stay where they are.

In 2022 alone, over 32 million people were displaced by weather-related disasters according to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. These numbers are expected to increase as the climate crisis intensifies. Entire island nations like Tuvalu and Kiribati face the very real threat of losing habitable land altogether, while coastal cities from Miami to Dhaka prepare for rising seas that could displace millions.

This blog explores what happens when the planet forces us to move. We will look at the root causes of climate migration, the regions most at risk, the human impact of displacement, and the political, ethical, and legal challenges of addressing it. More importantly, we’ll consider solutions—from climate adaptation to international agreements—that could help humanity navigate one of the greatest challenges of the 21st century.

What Causes Climate Migration?

The primary drivers of climate migration can be grouped into several categories: rising sea levels, extreme weather events, prolonged drought, and ecosystem collapse. While these causes may differ by geography, they all result in a shared outcome: communities that can no longer sustain life where they currently are.

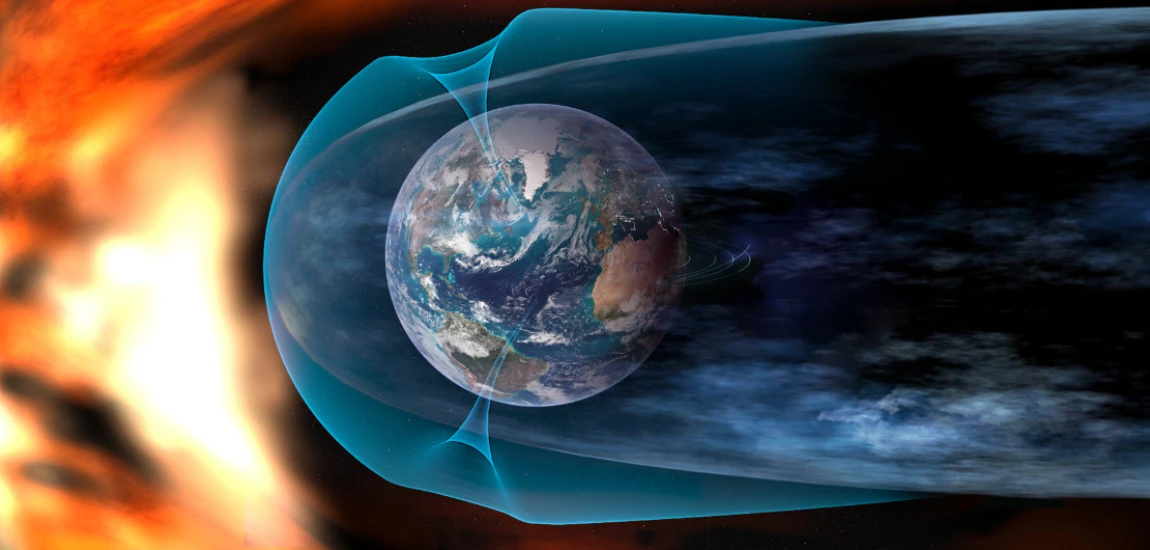

Rising Sea Levels: Melting glaciers and thermal expansion of oceans are swallowing coastlines at alarming rates. Low-lying nations such as the Maldives and Bangladesh are on the frontlines, with millions of people already living under the shadow of disappearing land. For these communities, migration is not a choice—it’s survival.

Extreme Weather Events: Hurricanes, floods, and typhoons are becoming stronger and more frequent. For example, Hurricane Katrina displaced hundreds of thousands in the U.S., many of whom never returned to their original homes. In countries with weaker infrastructures, such as the Philippines or Mozambique, such storms cause mass displacement with devastating long-term impacts.

Drought and Food Insecurity: In sub-Saharan Africa, prolonged droughts have destroyed crops and livestock, fueling migration as families search for food and income. Similarly, in parts of Central America, climate-induced drought is pushing many toward the U.S. border in search of survival.

Ecosystem Collapse: Beyond direct disasters, climate change disrupts ecosystems in ways that undermine livelihoods. From coral bleaching affecting fishing communities to deforestation altering rainfall patterns, slow-onset environmental changes also drive migration.

Importantly, climate migration often intersects with political instability and economic fragility, making it difficult to separate climate as the sole cause. However, the scientific consensus is clear: without urgent action, environmental pressures will force tens of millions to migrate every year.

Who Is Most Affected by Climate Migration?

While climate change is a global problem, its impacts are uneven. The most vulnerable populations often contribute the least to greenhouse gas emissions, yet they face the most severe consequences.

Small Island Nations: Countries like Kiribati, Tuvalu, and the Marshall Islands risk becoming uninhabitable within decades. Their citizens may become the world’s first “climate refugees” without formal protections under international law.

Developing Countries: Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and parts of Latin America are particularly vulnerable. Weak infrastructure, limited financial resources, and high population densities make these regions hotspots for climate displacement. For instance, in Bangladesh, flooding displaces millions annually, pushing many into overcrowded urban centers.

Urban Poor: Even in wealthy countries, marginalized communities are more likely to live in flood-prone areas, poorly built housing, or regions with limited disaster response systems. Hurricane Harvey in Houston highlighted how socio-economic inequality determines who can recover—and who cannot—after climate disasters.

Indigenous Communities: Many Indigenous peoples rely directly on their land for survival, whether through farming, fishing, or herding. As climate disrupts ecosystems, their cultural heritage and way of life are at risk of extinction.

The injustice lies in the fact that those most affected often lack the political power, economic resources, or international representation to advocate for their rights. Climate migration, therefore, is not only an environmental issue but also a profound question of global justice.

Legal and Ethical Challenges of Climate Migration

One of the biggest challenges with climate migration is the lack of legal recognition. Under the 1951 Refugee Convention, people fleeing environmental disasters are not considered “refugees.” This means they do not qualify for the same protections as those fleeing war or political persecution.

This raises critical ethical questions: Should the international community redefine what it means to be a refugee in the age of climate change? Who bears responsibility for assisting displaced populations—especially when wealthier nations are historically the largest emitters of greenhouse gases?

Some governments have begun addressing these gaps. New Zealand, for instance, has explored offering residency to Pacific Islanders displaced by rising seas. However, such efforts are isolated and far from comprehensive. Without a coordinated global framework, climate migrants risk falling into legal limbo, unable to claim asylum or access necessary support.

Beyond legality, there’s the ethical challenge of equity. Climate migration disproportionately affects poorer nations and vulnerable populations, raising questions of reparations, shared responsibility, and global solidarity. If emissions from industrialized countries are fueling displacement elsewhere, what obligations do those countries have to climate migrants?

In addition, internal migration poses challenges for governments already stretched thin. As rural populations move to urban centers, cities may face overcrowding, housing shortages, and social tensions, all of which require careful policy planning.

Solutions: Preparing for a World on the Move

While climate migration presents immense challenges, proactive steps can reduce risks and create pathways for resilience.

Climate Adaptation: Building resilient infrastructure, developing drought-resistant crops, and investing in early-warning systems can help communities withstand climate shocks. For example, mangrove restoration projects in Southeast Asia provide natural flood protection while sustaining local livelihoods.

Post-Disaster Support: Humanitarian aid must go beyond short-term relief to long-term rebuilding. Programs that support displaced families in regaining livelihoods, education, and housing are essential to avoid cycles of poverty and instability.

Legal Recognition: Updating international refugee frameworks to include climate migrants is crucial. Creating new visa categories or bilateral agreements could ensure people forced to move across borders have access to legal protection.

Global Cooperation: Climate migration cannot be addressed by any single nation. International funding mechanisms—such as the “loss and damage” fund agreed upon at COP27—must be expanded to help vulnerable countries manage displacement.

Community Engagement: Local voices must be at the heart of adaptation and migration planning. Empowering communities to participate in decision-making ensures solutions are culturally sensitive and sustainable.

Ultimately, preparing for climate migration means accepting that movement is inevitable in many cases. The goal should not be to prevent migration at all costs but to ensure that when it occurs, it happens with dignity, safety, and fairness.